Malapa: Technology and Fossil Preparation

Since his 2008 discovery of Malapa (the type site of Australopithecus sediba) using Google Earth, Professor Lee Berger’s projects have pushed the boundaries of technology for the field of palaeoanthropology. The research surrounding Malapa and Rising Star uses cutting-edge technology, much of it sourced right here in South Africa. Large multi-disciplinary teams are necessary for the interpretation of this material and serve to stoke the creativity of those involved. There is no such thing as “science as usual” when it comes to the research presented here!

Seeing Through RockMany of us have fantasized about having X-ray vision at one time or another, but with major advances in imaging technology, that is becoming closer to a reality. In the past, palaeontologists had to labour for weeks or even years, using dental drills and picks to recover precious fossil remnants encased in cement-like sediments. These scientists relied upon surface evidence of a fossil to guide them, as they chased the faint outline deeper and deeper into the rock. But what about fossils hidden deep inside that left no outward indication of their presence? These fossils went unknown and unrecovered—until now.

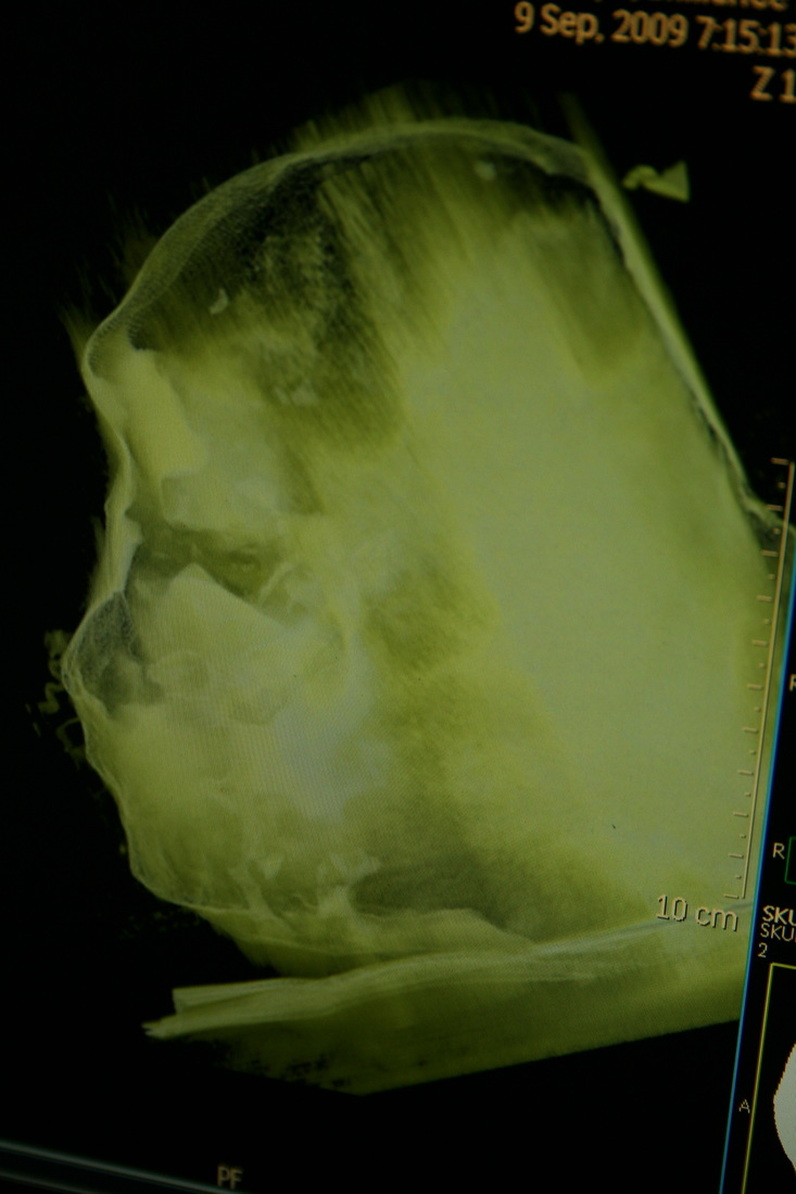

In February 2009, preparators were hard at work on a large block of calcified clastic sediments (fossilized soil) known to contain part of an upper arm bone belonging to MH1, when they unexpectedly encountered a portion of maxilla (upper jaw). In order to get a better look at this delicate bone before proceeding, the scientists involved decided to use a medical CT (computed tomography or CAT) scanner to generate 3D X-ray images. On April 21, 2009, the first CTs of Malapa blocks revealed that the maxilla was actually still attached to an entire juvenile cranium, the skull of MH1 that has become so iconic! Following that momentous discovery, more and more blocks of these concreted soils have undergone the same treatment: CT scanning prior to manual preparation. Blocks are chosen based on either visible bone or their location within the site and its potential for containing fossils.

|

|

Each block is colour-coded red, white, or yellow according to what the scans show (red = probable hominin or primate fossils; white = non-hominin or non-primate fossils; yellow = non-identifiable bone or no bone) and given a “B” number (for “block”) and a “UW88” number (for “University of the Witwatersrand” and Malapa’s site number). The resulting scans are then read by a trained radiologist, as fossil bones show up very differently than living bone and can be tricky to identify in digital scans.

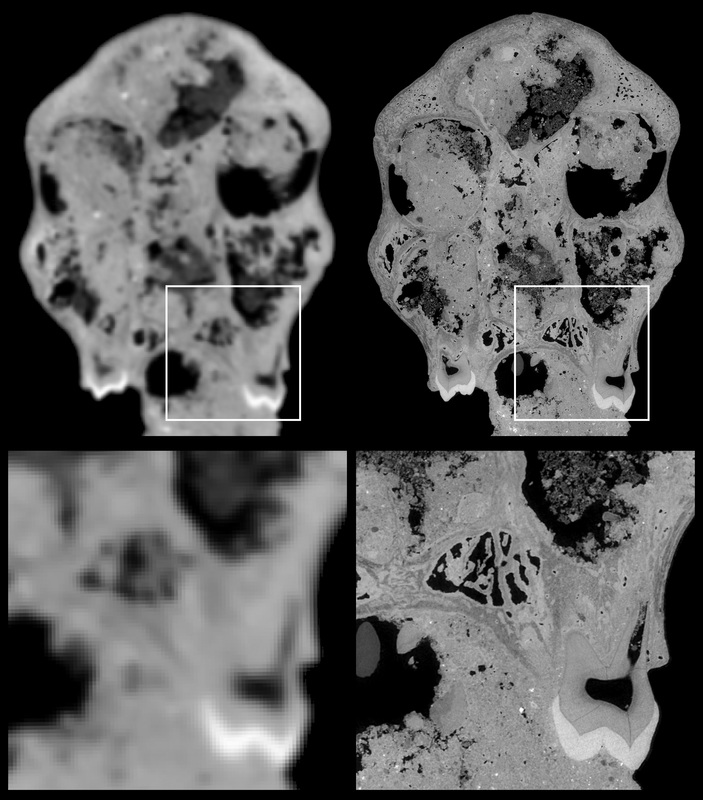

As the project has matured, ever more powerful tools have been added to gain better and better views within encasing rock. In 2010, phase contrast X-ray synchrotron microtomography was introduced. Synchrotron-generated light allows visualization within materials like standard CTs, but is more powerful than ordinary X-rays—100 BILLION times brighter than those produced at hospitals. This light is the result of highly energized electrons moving at high-speeds within a particle accelerator (called a synchrotron ). Unfortunately, the sheer size and complexity of such a synchrotron makes them exceedingly rare, so the relevant studies on the Malapa material has been performed at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France , through international collaboration. Because of its expense, synchrotron scans are reserved for key anatomical regions and particularly delicate problems, like generating the endocast of MH1.

|

Tools of the Trade

Whatever their source, digital scans give preparators a much needed heads up, reducing the number of surprises they encounter during manual preparation. For, while in some cases, where a fossil is very fragile, virtual preparation is possible, the majority of fossils are removed from the surrounding rock that entraps them. In the past, this process included the use of chisels, picks, dental drills, and/or acetic or other acids. Those unlucky workers were essentially flying blind when it came to excavating concreted blocks, and there is no telling how much material was damaged, destroyed, or simply missed.

Our preparators today have the advantage of high-powered 3D microscopes (like the one seen in use at the virtual lab), and are guided in their work by digital scans. These synchrotron or CT scans provide a kind of digital road map for them to follow so that nothing is missed. They have greatly improved the practice of manual preparation, reducing the frequency of potential accidents that occur when an unexpected fossil is encountered. And rather than harsh chemicals and rough picks and drills, the blocks removed at Malapa are prepared using compressed air drills known as “Air Scribes.” Occasionally, a kind of resin called paraloid is painted over the surface of a particularly fragile fossil in order to keep it in one piece.

Our preparators today have the advantage of high-powered 3D microscopes (like the one seen in use at the virtual lab), and are guided in their work by digital scans. These synchrotron or CT scans provide a kind of digital road map for them to follow so that nothing is missed. They have greatly improved the practice of manual preparation, reducing the frequency of potential accidents that occur when an unexpected fossil is encountered. And rather than harsh chemicals and rough picks and drills, the blocks removed at Malapa are prepared using compressed air drills known as “Air Scribes.” Occasionally, a kind of resin called paraloid is painted over the surface of a particularly fragile fossil in order to keep it in one piece.

Surprise!

On May 19, 2012, Berger was completing scanning for the day, when he decided to run a few extra blocks that were near the maximum size allowable. One of these blocks had been sitting and awaiting preparation since 2009. Once the scanning began, it was soon apparent that this block, Block 051, was no ordinary rock. It lit up within with the outline of a substantial hominin partial skeleton. Berger and his team now believe Block 051 to contain most of the missing left side of MH1, including a portion of the mandible (lower jaw). If true, this would make Karabo one of the most complete early fossil hominin skeletons ever discovered! Most amazing of all, is that none of the treasures within are visible from the outside of the block. Since that time, the team has applied CT scans not just to the imaging of known fossils, but to the discovery of fossils within blocks. For the first time in palaeoanthropological history, blocks are being chosen, not for visible traces, but solely for the potential fossils that they might contain.

Right Before Your Eyes

The incredible discovery within Block 051 sparked the virtual lab project you are viewing here today. True to the ethic of open access and communication that has characterized Berger’s work since Matthew’s discovery at Malapa, he decided that he couldn’t contain his excitement, and needed to share this with the world. But how do you share the preparation of a scientific specimen with a large audience? No one had ever tried to share the process of discovery before in such a manner as Berger envisioned. He wanted to reach the broadest possible audience in real time, but there were many things to consider. Fossil preparation isn’t exactly fast-paced, as it focuses on small details that can’t be rushed. It’s painstaking work that musn’t be disturbed. Berger and his team decided that such concerns warranted a novel approach to sharing, and out of that agreement, the virtual lab was born.

In October 2012, Berger announced the discovery of the remarkable remains within Block 051, as well as his conviction that these fossils would be prepared live over the internet. It was determined that the fossils would be prepared at Maropeng, the official visitor centre of the Cradle of Humankind (CoH) World Heritage Site, within a facility especially constructed for this purpose. Visitors at Maropeng are now, in a manner of speaking, able to peer over the shoulders of Wits preparators, as they engage in the detailed work of unlocking fossils from rock. You can listen in on their conversations and even peer down their microscopes using a digital feed. Whether you’re outside the lab window in Maropeng, or surfing the net on your couch at home, you won’t just feel like part of the process of discovery, you will be!

The incredible discovery within Block 051 sparked the virtual lab project you are viewing here today. True to the ethic of open access and communication that has characterized Berger’s work since Matthew’s discovery at Malapa, he decided that he couldn’t contain his excitement, and needed to share this with the world. But how do you share the preparation of a scientific specimen with a large audience? No one had ever tried to share the process of discovery before in such a manner as Berger envisioned. He wanted to reach the broadest possible audience in real time, but there were many things to consider. Fossil preparation isn’t exactly fast-paced, as it focuses on small details that can’t be rushed. It’s painstaking work that musn’t be disturbed. Berger and his team decided that such concerns warranted a novel approach to sharing, and out of that agreement, the virtual lab was born.

In October 2012, Berger announced the discovery of the remarkable remains within Block 051, as well as his conviction that these fossils would be prepared live over the internet. It was determined that the fossils would be prepared at Maropeng, the official visitor centre of the Cradle of Humanind (CoH) World Heritage Site , within a facility especially constructed for this purpose. Visitors at Maropeng are now, in a manner of speaking, able to peer over the shoulders of Wits preparators, as they engage in the detailed work of unlocking fossils from rock. You can listen in on their conversations and even peer down their microscopes using a digital feed. Whether you’re outside the lab window in Maropeng, or surfing the net on your couch at home, you won’t just feel like part of the process of discovery, you will be!

In October 2012, Berger announced the discovery of the remarkable remains within Block 051, as well as his conviction that these fossils would be prepared live over the internet. It was determined that the fossils would be prepared at Maropeng, the official visitor centre of the Cradle of Humankind (CoH) World Heritage Site, within a facility especially constructed for this purpose. Visitors at Maropeng are now, in a manner of speaking, able to peer over the shoulders of Wits preparators, as they engage in the detailed work of unlocking fossils from rock. You can listen in on their conversations and even peer down their microscopes using a digital feed. Whether you’re outside the lab window in Maropeng, or surfing the net on your couch at home, you won’t just feel like part of the process of discovery, you will be!

The incredible discovery within Block 051 sparked the virtual lab project you are viewing here today. True to the ethic of open access and communication that has characterized Berger’s work since Matthew’s discovery at Malapa, he decided that he couldn’t contain his excitement, and needed to share this with the world. But how do you share the preparation of a scientific specimen with a large audience? No one had ever tried to share the process of discovery before in such a manner as Berger envisioned. He wanted to reach the broadest possible audience in real time, but there were many things to consider. Fossil preparation isn’t exactly fast-paced, as it focuses on small details that can’t be rushed. It’s painstaking work that musn’t be disturbed. Berger and his team decided that such concerns warranted a novel approach to sharing, and out of that agreement, the virtual lab was born.

In October 2012, Berger announced the discovery of the remarkable remains within Block 051, as well as his conviction that these fossils would be prepared live over the internet. It was determined that the fossils would be prepared at Maropeng, the official visitor centre of the Cradle of Humanind (CoH) World Heritage Site , within a facility especially constructed for this purpose. Visitors at Maropeng are now, in a manner of speaking, able to peer over the shoulders of Wits preparators, as they engage in the detailed work of unlocking fossils from rock. You can listen in on their conversations and even peer down their microscopes using a digital feed. Whether you’re outside the lab window in Maropeng, or surfing the net on your couch at home, you won’t just feel like part of the process of discovery, you will be!