Meet Homo naledi

Since its announcement in September 2015, Homo naledi has become a source of wonder and contention for scientists and lay people alike. The unique suite of characteristics expressed throughout the skeletons of the 15 individuals recovered to date, reveal a complex mosaic of traits that are both more ancestral and those more derived. It is the job of palaeoanthropologists to recognize, describe, and interpret these traits to determine the place of this new species within the human lineage and to shed light on the past lives of our ancestors.

What’s in a Name?

It is a very serious undertaking to name a new species, such as Homo naledi, and not one that is taken lightly. Most of the fossil hominin record is fragmentary in nature, making it sometimes difficult for comparisons of skeletal elements to be made. In fact, it has often been remarked that had many of the elements recovered from within the Dinaledi Chamber been found alone, it would have been easy to mistake them for another hominin. In that case, how can one be sure that the bones found in the Dinaledi Chamber belong to only one species or that Homo naledi is a new hominin at all? Fortunately, as you’ll see below, the sheer amount of fossils recovered, as well as their completeness, makes the team of researchers who have studied the original remains very confident in their assessments based on the material to date.

The Dinaledi Chamber has yielded the largest and most complete early hominin assemblage of a single species in the 150-year history of hominin fossil discovery. The 15 individuals identified from the over 1550 remains have yielded 737 partial or complete anatomical elements (nearly every element in the skeleton), with most elements repeated multiple times. Some elements were even found in articulation, meaning that it is not possible that the mosaic of traits results from a jumble of different species. The bones that make up the skeletons of Homo naledi come from both young and old, and all are more alike one another than they are similar to any other hominin group to which they have been compared. The only significant variation seen within the Dinaledi hominins is what would be expected relative to sex or body size. Furthermore, the unique traits exhibited by Homo naledi to the exclusion of other hominin groups do not appear to be pathological, but rather functional or species-specific characteristics. Of these 15 individuals, 5 clearly associated remains have been identified and designated Dinaledi Hominins 1 through 5 (DH1 through 5).

The Dinaledi Chamber has yielded the largest and most complete early hominin assemblage of a single species in the 150-year history of hominin fossil discovery. The 15 individuals identified from the over 1550 remains have yielded 737 partial or complete anatomical elements (nearly every element in the skeleton), with most elements repeated multiple times. Some elements were even found in articulation, meaning that it is not possible that the mosaic of traits results from a jumble of different species. The bones that make up the skeletons of Homo naledi come from both young and old, and all are more alike one another than they are similar to any other hominin group to which they have been compared. The only significant variation seen within the Dinaledi hominins is what would be expected relative to sex or body size. Furthermore, the unique traits exhibited by Homo naledi to the exclusion of other hominin groups do not appear to be pathological, but rather functional or species-specific characteristics. Of these 15 individuals, 5 clearly associated remains have been identified and designated Dinaledi Hominins 1 through 5 (DH1 through 5).

Top to Toe Anatomy

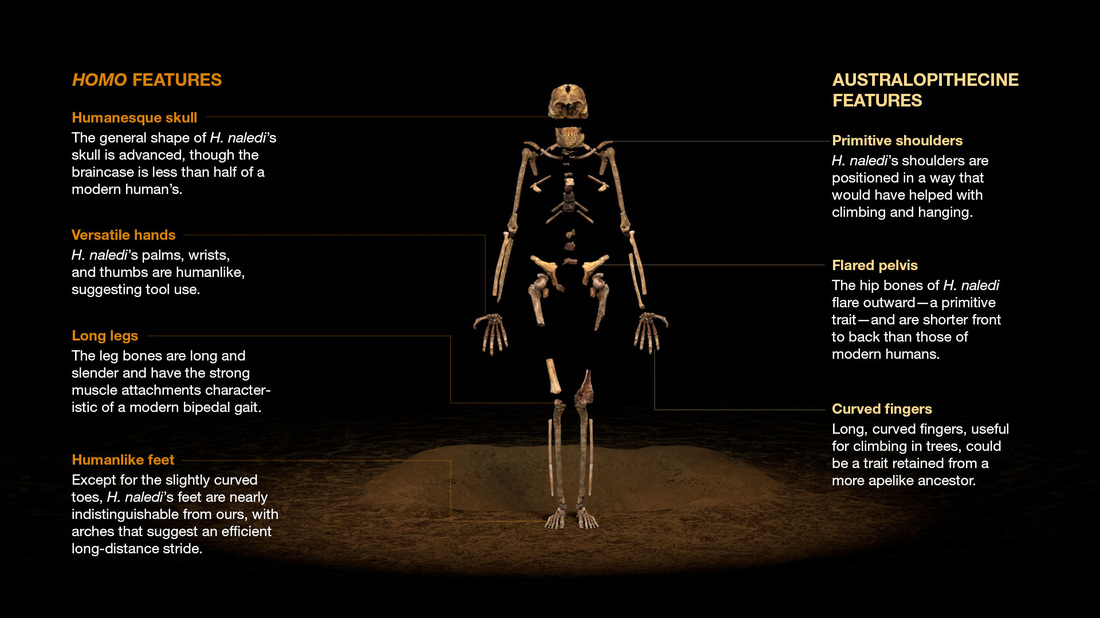

Homo naledi is comparable in height and weight to small-bodied modern humans (144.5-147.8 cm/4’9”-4’10” tall, weighing 39.7-55.8 kg/87.5-123 lbs), but it is there that comparisons diverge. The skeleton of Homo naledi is a unique mosaic of australopithecine features, more Homo-like features (particularly those traits most evident in the earliest members of our genus), and features previously unknown for any hominin and unique to the species itself. The expression of these more ancestral and more derived traits is distributed throughout the body, but can be roughly characterised as the following:

- Homo-like skull and teeth

- Homo-like spine

- Homo-like arms and legs

- Homo-like feet and ankles

- Australopithecine-like brain size

- Australopithecine-like shoulder and ribcage

- Australopithecine-like pelvis

- Uniquely curved fingers

Future Directions

To date, there are three anatomy-oriented papers published on Homo naledi: the initial description and naming of the new species, as well as a specialty paper each on the hands and feet (all open access). Additional regional anatomy papers are in preparation, with previews presented at the 85th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (AAPA) in Atlanta, Georgia (USA) in April 2016. Details of these analyses will be added to this page as they are made available.

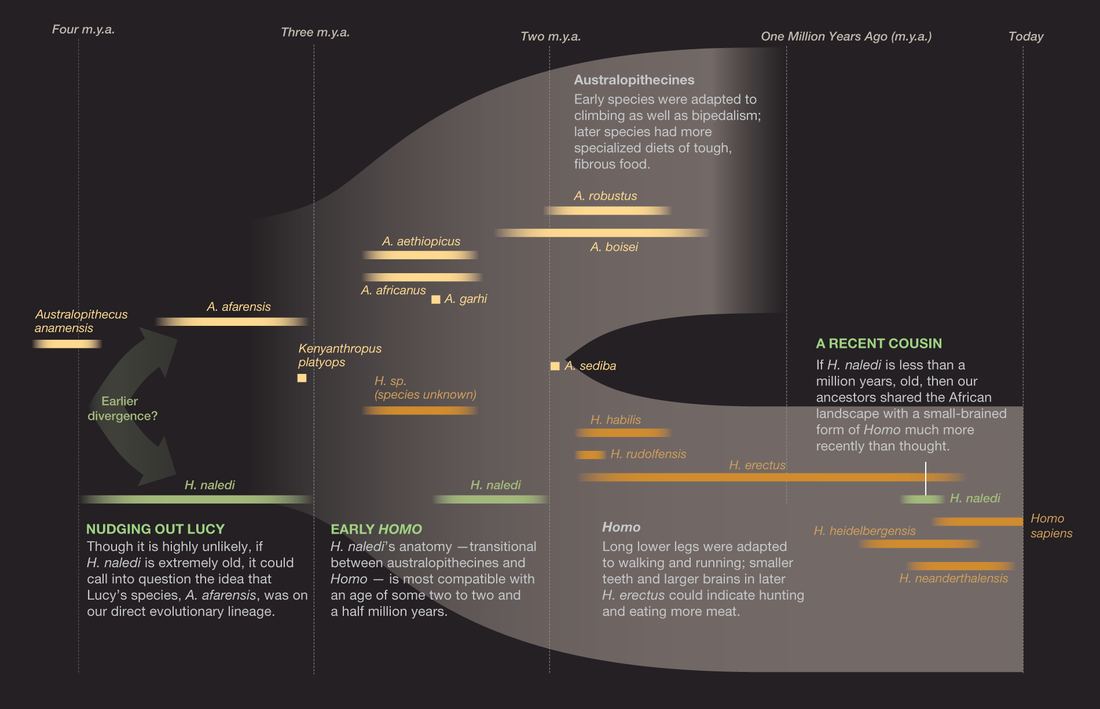

In the meantime, efforts continue to date the Dinaledi fossils in order to assemble more robust interpretations of how this species fits in the grand scheme of human evolution. Based on the anatomy described here, and in the absence of dates, it is estimated that the lineage to which Homo naledi belongs originated around 2 to 2.5 million years ago. This assessment is based on the transitional nature of the expressed traits, which give the appearance of a creature no longer australopithecine, but not yet human.

In the meantime, efforts continue to date the Dinaledi fossils in order to assemble more robust interpretations of how this species fits in the grand scheme of human evolution. Based on the anatomy described here, and in the absence of dates, it is estimated that the lineage to which Homo naledi belongs originated around 2 to 2.5 million years ago. This assessment is based on the transitional nature of the expressed traits, which give the appearance of a creature no longer australopithecine, but not yet human.

Bibliography - Rising Star/Homo naledi

Berger, Lee R., et al. “Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa.” eLife 4 (2015): e09560.

[Full text]

Dembo, Mana, et al. “The evolutionary relationships and age of Homo naledi: An assessment using dated Bayesian phylogenetic methods.” Journal of Human Evolution 97 (2016): 17-26.

[Abstract only]

Dirks, Paul H. G. M., et al. “Geological and taphonomic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa.” eLife 4 (2015): e09561.

[Full text]

Dirks, Paul H. G. M., et al. “Comment on ‘Deliberate body disposal by hominins in the Dinaledi Chamber, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa?’”[J. Hum. Evol. 96 (2016) 145-148]." Journal of Human Evolution 96 (2016): 149.

[Abstract only]

Harcourt-Smith, William E. H., et al. “The foot of Homo naledi.” Nature Communications 6 (2015).

[Full text]

Hawks, John. “The Latest on Homo naledi: A recent addition to the human family tree doesn't fit in clearly yet.” (2016): 198-200.

[Full text]

Hawks, John, and Lee R. Berger. “The impact of a date for understanding the importance of Homo naledi.” Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa (2016): 1-4.

[Abstract only]

Kivell, Tracy L., et al. “The hand of Homo naledi.” Nature Communications 6 (2015).

[Full text]

Kruger, Ashley, Patrick S. Randolph-Quinney, and Marina Elliott. “Multimodal spatial mapping and visualisation of Dinaledi Chamber and Rising Star Cave.” South African Journal of Science 112.5-6 (2016): 1-11.

[Full text]

Randolph-Quinney, Patrick S. “A new star rising: Biology and mortuary behaviour of Homo naledi.” South African Journal of Science 111.9-10 (2015): 1-4.

[Full text]

Randolph-Quinney, Patrick S. “The mournful ape: Conflating expression and meaning in the mortuary behaviour of Homo naledi.” South African Journal of Science 111.11-12 (2015): 1-5.

[Full text]

Stringer, Chris. “The many mysteries of Homo naledi.” eLife 4 (2015): e10627.

[Full text]

Thackeray, Francis J. “Estimating the age and affinities of Homo naledi.” South African Journal of Science 111.11-12 (2015): 1-2.

[Full text]

Thackeray, Francis J. “The possibility of lichen growth on bones of Homo naledi: Were they exposed to light?” South African Journal of Science 112.7-8 (2016): 1-5.

[Full text]

Randolph-Quinney, Patrick S., et al. "Response to Thackeray (2016) - The possibility of lichen growth on bones of Homo naledi: were the exposed to light?: commentary." South African Journal of Science 112.9 & 10 (2016): 16-20.

[Full text]

Feuerriegel, Elen M., et al. "The upper limb of Homo naledi." Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.

[Abstract only]

Laird, Myra F., et al. "The skull of Homo naledi."Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.

[Abstract only]

Marchi, Damiano, et al. "The thigh and leg of Homo naledi." Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.

[Abstract only]

Schroeder, Lauren, et al. "Skull diversity in the Homo lineage and the relative position of Homo naledi." Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.1

[Full text]

Dembo, Mana, et al. “The evolutionary relationships and age of Homo naledi: An assessment using dated Bayesian phylogenetic methods.” Journal of Human Evolution 97 (2016): 17-26.

[Abstract only]

Dirks, Paul H. G. M., et al. “Geological and taphonomic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa.” eLife 4 (2015): e09561.

[Full text]

Dirks, Paul H. G. M., et al. “Comment on ‘Deliberate body disposal by hominins in the Dinaledi Chamber, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa?’”[J. Hum. Evol. 96 (2016) 145-148]." Journal of Human Evolution 96 (2016): 149.

[Abstract only]

Harcourt-Smith, William E. H., et al. “The foot of Homo naledi.” Nature Communications 6 (2015).

[Full text]

Hawks, John. “The Latest on Homo naledi: A recent addition to the human family tree doesn't fit in clearly yet.” (2016): 198-200.

[Full text]

Hawks, John, and Lee R. Berger. “The impact of a date for understanding the importance of Homo naledi.” Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa (2016): 1-4.

[Abstract only]

Kivell, Tracy L., et al. “The hand of Homo naledi.” Nature Communications 6 (2015).

[Full text]

Kruger, Ashley, Patrick S. Randolph-Quinney, and Marina Elliott. “Multimodal spatial mapping and visualisation of Dinaledi Chamber and Rising Star Cave.” South African Journal of Science 112.5-6 (2016): 1-11.

[Full text]

Randolph-Quinney, Patrick S. “A new star rising: Biology and mortuary behaviour of Homo naledi.” South African Journal of Science 111.9-10 (2015): 1-4.

[Full text]

Randolph-Quinney, Patrick S. “The mournful ape: Conflating expression and meaning in the mortuary behaviour of Homo naledi.” South African Journal of Science 111.11-12 (2015): 1-5.

[Full text]

Stringer, Chris. “The many mysteries of Homo naledi.” eLife 4 (2015): e10627.

[Full text]

Thackeray, Francis J. “Estimating the age and affinities of Homo naledi.” South African Journal of Science 111.11-12 (2015): 1-2.

[Full text]

Thackeray, Francis J. “The possibility of lichen growth on bones of Homo naledi: Were they exposed to light?” South African Journal of Science 112.7-8 (2016): 1-5.

[Full text]

Randolph-Quinney, Patrick S., et al. "Response to Thackeray (2016) - The possibility of lichen growth on bones of Homo naledi: were the exposed to light?: commentary." South African Journal of Science 112.9 & 10 (2016): 16-20.

[Full text]

Feuerriegel, Elen M., et al. "The upper limb of Homo naledi." Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.

[Abstract only]

Laird, Myra F., et al. "The skull of Homo naledi."Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.

[Abstract only]

Marchi, Damiano, et al. "The thigh and leg of Homo naledi." Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.

[Abstract only]

Schroeder, Lauren, et al. "Skull diversity in the Homo lineage and the relative position of Homo naledi." Journal of Human Evolution (2016), in press.1